Anyone who’s ever tried to quit smoking, eat less or exercise more knows that changing personal habits is hard. Habits are the behavioral equivalent of mental heuristics—short cuts that allow our brain to chug along on autopilot.

The more often we repeat a routine behavior, the less we need to think about it. That’s one reason why entrenched behaviors are notoriously difficult to change—they happen without thinking.

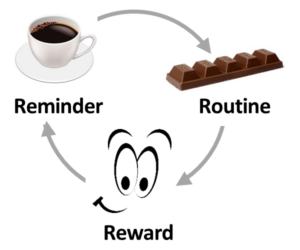

The Habit Formation Loop

Habits are formed by a loop consisting of a reminder, a routine and a reward. The reminder serves as a cue for a specific behavior. Once we perform the routine behavior, our brain “rewards” us with a burst of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Over time, we learn to anticipate the reward as soon as the reminder appears. When it does, we experience a strong urge to perform the routine.

For example, I have a habit of eating a chocolate bar every day with my coffee after lunch. Coffee is the reminder, eating chocolate is the routine, and the rush of glucose (and dopamine) is the reward.

This habit is difficult to extinguish! The mere presence of the reminder is enough to push me headfirst into the routine. Smell coffee? Eat chocolate!

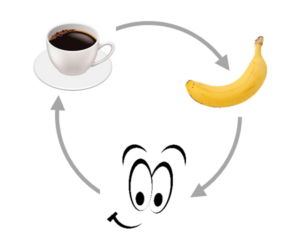

Instead of eating a chocolate bar, I can substitute a healthier routine such as eating a banana—or going for a walk.

The hardest part in breaking a habit is to identify the real trigger for the routine behavior. Is drinking coffee the trigger for my chocolate craving? Or is it seeing the shiny vending machines in the cafeteria?

If it’s the vending machines, I could break my habit by walking to a coffee shop down the street instead of the cafeteria. Although this would present the immediate danger of eating a lemon poppy seed muffin instead of chocolate. As Gilda Radner said, “It just goes to show you, it’s always something—if it ain’t one thing, it’s another.” ?

The Story of Sam

Sam is a team leader at an insurance company. With the precision of a Swiss watch, Sam appears in his deputy’s office each day at 5:30 pm and asks her how the day went. Sam’s behavior is motivated by good reasons—he wants to show that he cares and keep informed about her work. However, Sam’s habit of appearing at exactly 5:30 pm does not produce the desired effect. The deputy thinks Sam is checking when she leaves the office.

Sam breaks the habit by substituting a different routine. Instead of visiting his deputy, Sam spends 15 minutes writing down what he has accomplished and his priority for the next day.

The new behavioral routine of reflecting and planning provides the expected reward. The good news is that Sam is still free to visit his deputy. He just doesn’t feel compelled to do so every day at 5:30 pm. He may experiment with other ways to connect with his team. He might decide to visit a team member at a different time each day. Or he could plan a surprise ice cream break for the whole team.

References

Clear, J. (2016). Transform Your Habits: The Science of How to Stick to Good Habits and Break Bad Ones, 3rd Edition. Retrieved from jamesclear.com.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. New York. Random House.

Graybiel, A. M. (2008). Habits, Rituals, and the Evaluative Brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience 31, 359-87.

Schultz, W., Dayan, P., & Montague, P. R. (1997). A Neural Substrate of Prediction and Reward. Science 275, 14 March, 1593-99.

Images courtesy of Pixabay CC0, Clipartsgram.com, Public Domain